Agent UX: Undo/Redo fails in the Age of AI

The Problem: Undo/Redo Was Built for a Different Era

Undo/redo is breaking. Not subtly degrading—breaking.

As someone who's spent years building collaborative editing systems and watching AI transform how we interact with documents, I've watched users hit Ctrl+Z expecting predictable behavior and instead get something that erodes trust. The undo/redo mechanism, one of the most fundamental user interface conventions we inherit from the 1970s, assumes a world that no longer exists: one person editing one document at a time.

Today, multiple agents (humans, AI assistants, collaborators, background processes) simultaneously edit shared documents. The linear stack model that powers every text editor, design tool, and collaborative app becomes not just inadequate—it becomes actively harmful to user experience, creating unpredictable behavior that makes users feel like they've lost control.

This isn't theoretical. I've seen it break in production systems. This essay demonstrates why this breakdown is architecturally inevitable, shows the precise technical moments where it fails, and proposes UX solutions that can restore user agency in multi-agent environments.

Hello, this is Nils 👋. I'm a product engineer obsessed with agent UX. This research comes from years of building collaborative systems. At Legit, we're building infrastructure for AI collaboration with control, and this problem sits at the heart of what we're solving. If you're wrestling with similar challenges in design, engineering, or product development, I'd love to hear your thoughts.

Why Undo/Redo Works So Well (Until It Doesn't)

The Linear Stack Model

Traditional undo/redo systems work because they implement a beautifully simple, elegant stack:

javascript// Traditional undo stack const undoStack = [operation1, operation2, operation3, ...]; // When user presses Ctrl+Z: const lastOperation = undoStack.pop(); const inverseOperation = lastOperation.getInverse(); inverseOperation.apply();

This creates predictable UX because:

- One user, one timeline: Clear "last operation" with no ambiguity

- Sequential operations: Each undo moves backward in time, maintaining causal chain

- Atomic changes: Each operation is self-contained and reversible

The stack model works perfectly when one person edits one document. Users develop a mental model: "Press Ctrl+Z to go back one step." This predictability is what makes undo/redo feel like a cognitive extension—users don't think about it, they just use it. That's the hallmark of great UX: invisible when it works, catastrophic when it breaks.

Why We Need Graphs: The Multi-Agent Reality

The Problem: Multiple Agents, Multiple Timelines

Modern collaborative software operates under fundamentally different constraints:

javascript// Concurrent operations from multiple agents const operations = { user: [op1, op2, op3], ai: [op4, op5], collaborator: [op6, op7, op8], background: [op9] }; // When user presses Ctrl+Z: which operation to undo?

The stack model cannot resolve this ambiguity because it conflates temporal order with causal responsibility. This is a fundamental architectural limitation: in a multi-agent system, the "last operation" (by timestamp) may not be the operation the user wants to undo (by intent).

The system knows when things happened, but it doesn't know who intended them or what the user's mental model expects. This mismatch between system state and user intent is where trust erodes.

Where UX Breaks: The Attribution Problem

Consider this real scenario that I've watched users encounter:

- User edits paragraph A (their change)

- AI assistant rewrites paragraph B (AI change, happens milliseconds later)

- User edits paragraph C (their change)

- User presses Ctrl+Z

User's mental model: "I just edited paragraph C, so Ctrl+Z should undo my paragraph C edit" System's behavior: "The most recent operation was the AI's paragraph B rewrite, so I'll undo that" User's experience: Confusion, then frustration, then distrust

This creates a trust breakdown that compounds. The first time, users think "huh, that's weird." The second time, they start questioning whether they can trust the system. By the third time, they stop using undo/redo entirely, which means they stop experimenting, which means your product loses one of its most valuable affordances.

The deeper issue is that undo/redo isn't just a feature—it's a safety net that enables exploration. When users can't predict its behavior, they become risk-averse. They stop trying new things. This kills product velocity at the user level.

The Technical Depth: Why Redo Becomes Impossible

While undo navigation is complex, redo becomes fundamentally impossible in graph-based systems:

schematicGraph State After Undo: A (user edit) / \ B C (AI edit) ← UNDONE | | D E (collaborator edit) \ / F (merge) Question: What should redo do? - Redo the AI edit (C)? - Redo the collaborator edit (E)? - Redo the merge (F)? - Redo along which path?

The Fundamental Issue: Redo assumes a linear future—one timeline you're "undoing forward" through—but graphs have multiple possible futures. There's no single "forward" direction. This isn't just a UI problem; it's an architectural impossibility with linear state models.

From a product perspective, this means that once you enter a multi-agent system, redo stops being a feature and starts being a promise you can't keep. Better to remove it entirely than to ship broken behavior that erodes trust.

Two UX Solutions: How to Make Graphs Work

The technical foundation exists—version control systems (Git, Mercurial) have proven that graph-based history works at scale. The challenge isn't the data structure; it's translating these concepts into intuitive user interfaces that don't expose the complexity.

As a product engineer, I'm interested in solutions that maintain user agency without overwhelming users with graph theory. Here are two approaches I've prototyped and tested:

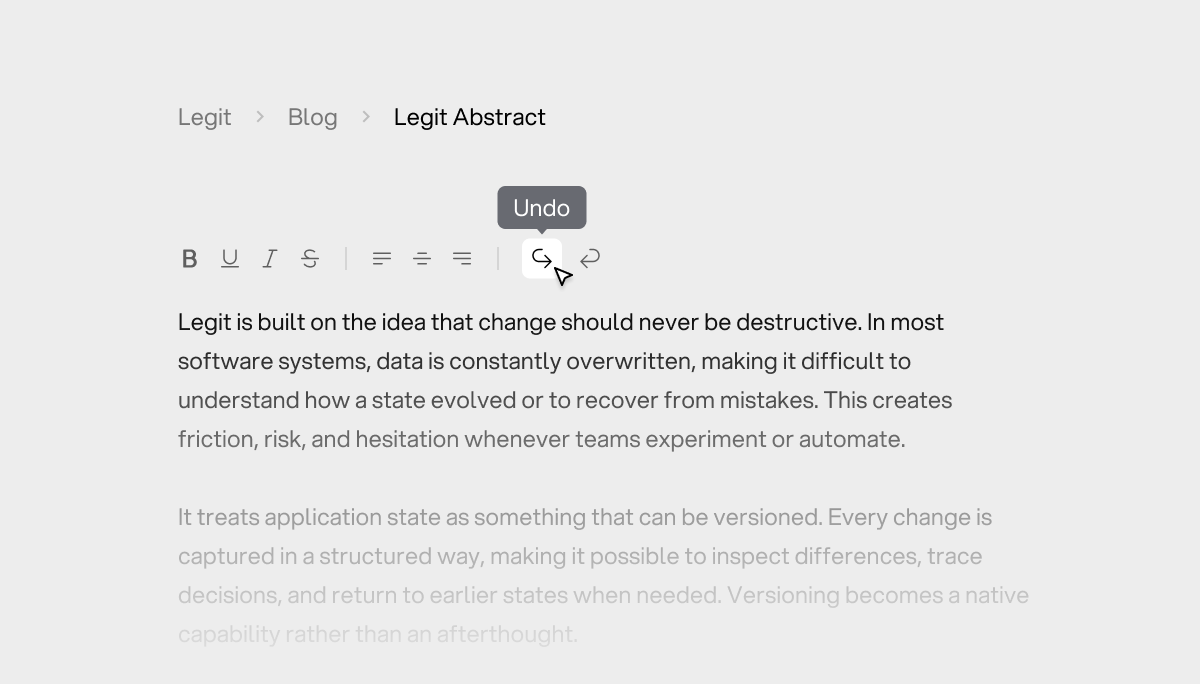

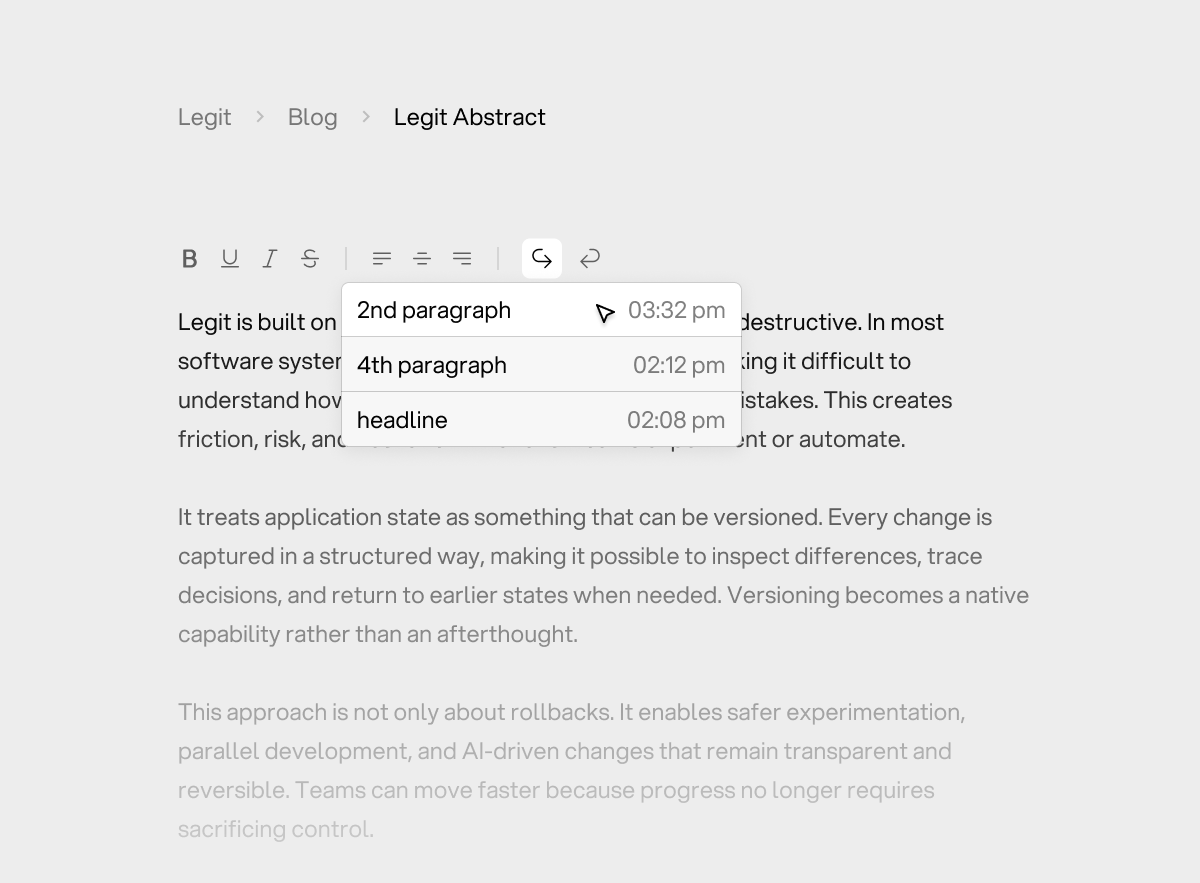

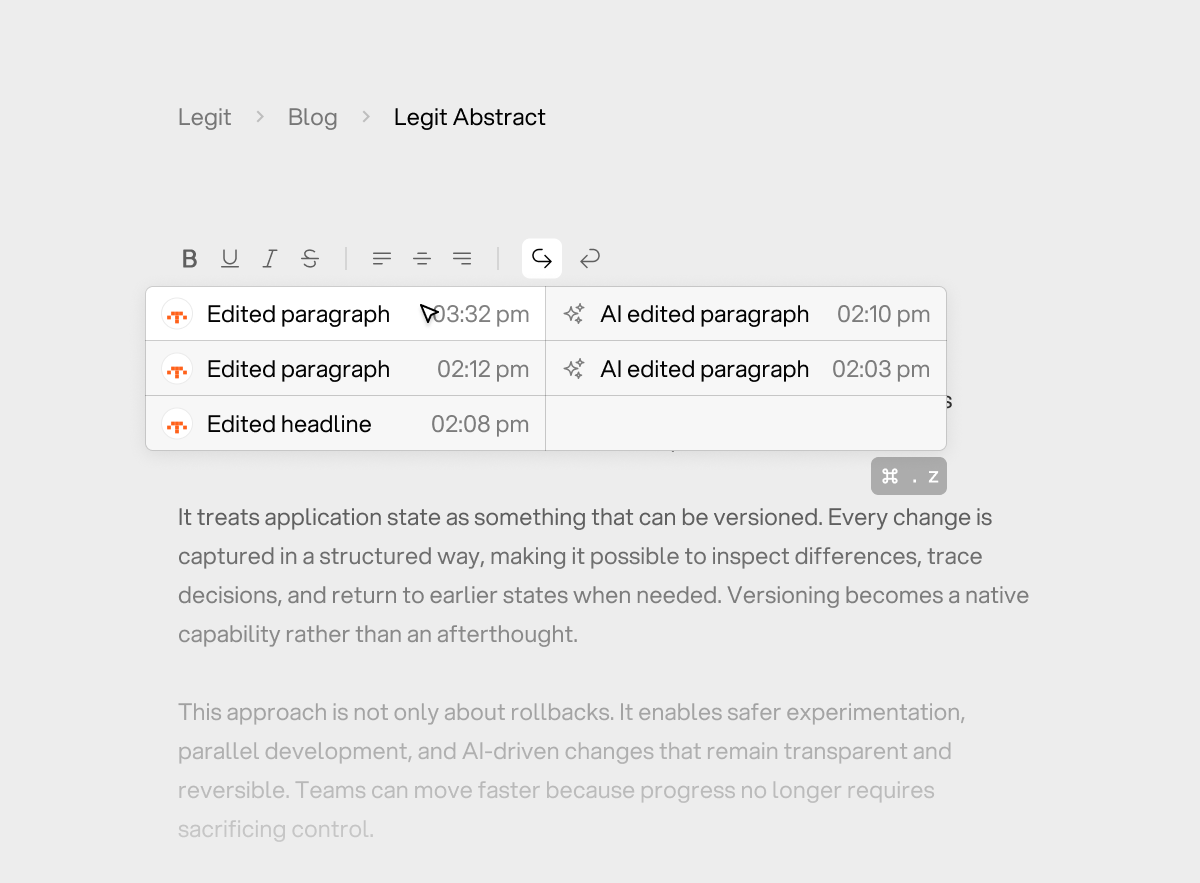

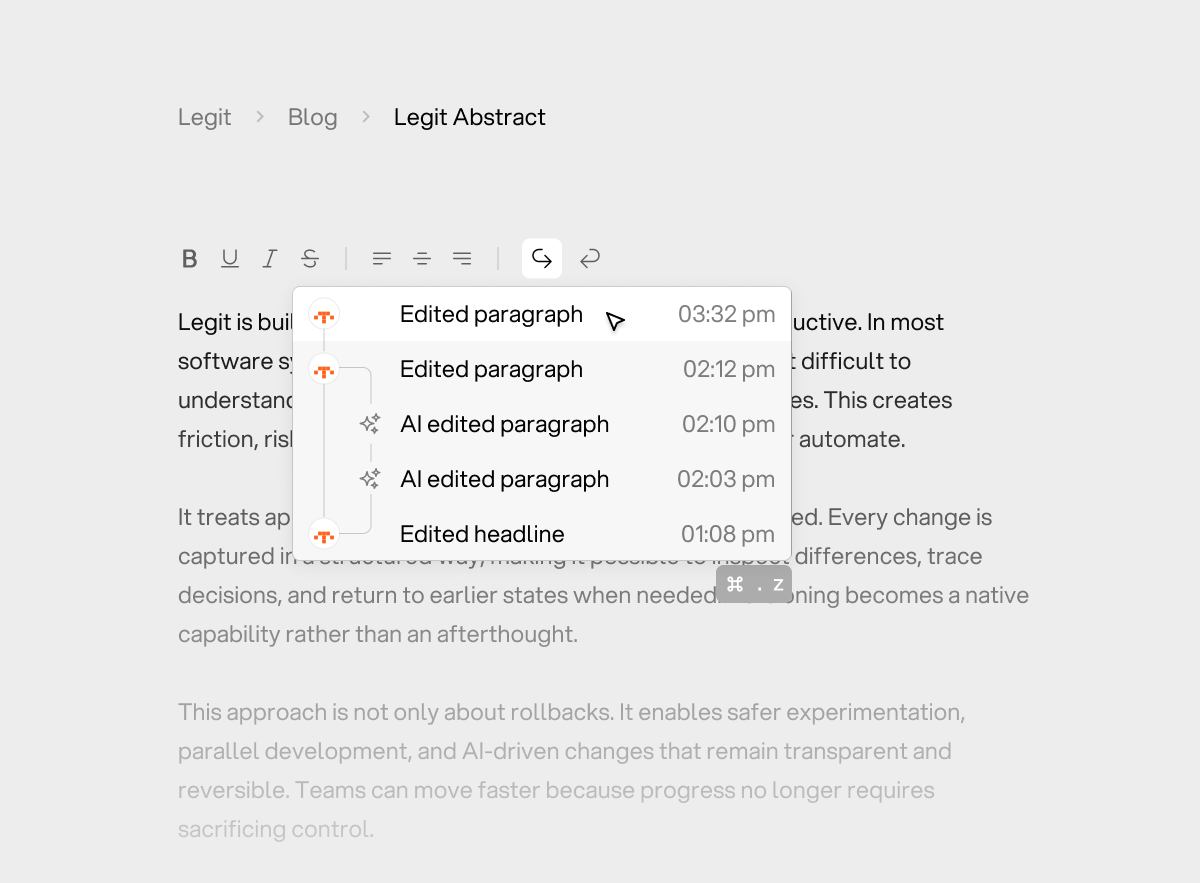

Solution 1: Multi-Path Undo Systems

Concept: Each agent (human, AI, collaborator) maintains a separate undo path. Users can choose which path to navigate.

How it works:

- Default behavior: Ctrl+Z undoes the user's most recent action (maintaining personal control)

- Extended interaction: Users can expand a dropdown or use a modifier key to see all undo paths

- Path visualization: Each agent's changes are visually attributed, so users understand who changed what

- Smart defaults: The system can infer likely intent (e.g., "user probably wants to undo their own change, not the AI's")

UX Benefits:

- Maintains the muscle memory of traditional undo/redo

- Gives users agency to choose which timeline to navigate

- Reduces attribution confusion without exposing full graph complexity

- Scales from single-user to highly collaborative scenarios

Trade-offs to consider:

- More complex state management (multiple stacks or graphs)

- UI real estate for path selection (hidden by default, revealed on demand)

- Education curve (users need to discover multi-path capabilities)

Solution 2: Visual History Graphs

Concept: Every change becomes a node in an interactive, visual graph. Users can hover to see attribution, context, and reasoning, then roll back to any branch point.

How it works:

- Timeline visualization shows change flow, branching, and merges

- Hover states reveal change context, attribution, and (for AI) reasoning

- Click-to-navigate allows users to jump to any point in history

- Merge conflicts are clearly visualized, not hidden

- Diff previews show what would change before committing to navigation

UX Benefits:

- Complete transparency: users understand causality and can see the full story

- Powerful for debugging complex changes or understanding AI behavior

- Builds trust through visibility rather than hiding complexity

- Enables sophisticated workflows (e.g., "revert to before AI made that change, then selectively re-apply parts")

Trade-offs to consider:

- Higher cognitive load (users need to parse graphs)

- Slower interaction (visual navigation vs. instant Ctrl+Z)

- Requires more sophisticated UI components

- Best suited for power users or specific use cases (e.g., code editing, document review)

When to use: This is the "power user" solution—appropriate for tools where users need to understand change causality or debug complex multi-agent interactions.

Product Engineering Note: These aren't mutually exclusive. You might ship Solution 1 as the default (fast, familiar) and Solution 2 as an advanced mode (powerful, transparent). The key is matching the complexity to the user's needs and the system's edit rate.

A More Honest Take: You Probably Don't Need a Graph (Until You Do)

It's tempting to jump straight from "undo is broken" to "we need full history graphs everywhere".

Graph-based histories come with real costs: in code complexity, in UX cognitive load, in performance, and in time-to-market. For many products, adopting them too early is unnecessary overengineering that slows you down and confuses users.

The real answer is more uncomfortable but more honest:

"Undo/redo design depends on the shape of your system and ignoring that is the real risk."

As a product engineer, this is the part I find most interesting: knowing when to invest in complexity. Not because it's cool (graphs are cool), but because the system's edit rate and actor count have reached a threshold where the old model actively harms users.

The Hidden Cost of Graphs

History graphs introduce complexity at multiple layers, and as a product engineer, you need to account for all of them:

Engineering Complexity:

- Non-linear state resolution: Merging operations becomes non-trivial; you need conflict resolution algorithms

- Conflict handling: Deciding what to do when two agents modify the same region simultaneously

- Storage and performance trade-offs: Graphs grow faster than stacks; you need efficient delta compression

- Hard-to-test edge cases: Concurrency bugs, race conditions, partial merges—all the fun distributed systems problems

- Operational overhead: Graph state can be harder to debug, audit, and migrate

UX Complexity:

- Visual noise: Graphs can overwhelm users who just want to undo a typo

- Higher cognitive load: Users need to understand branching, merging, attribution

- Decision fatigue: More choices at moments where users expect speed and predictability

- Risk of exposing internal complexity too early: Users don't need to see your CRDT implementation

- Onboarding friction: New users need to learn new mental models

Product Complexity:

- Feature velocity: More complex systems take longer to build, test, and iterate

- Support burden: Users will find edge cases you didn't anticipate

- Maintenance debt: Graph systems are harder to refactor as requirements change

When Linear Stacks Are Still Correct:

For products with:

- Low edit frequency (few operations per minute)

- Single-user workflows (or limited collaboration)

- Limited automation (few background processes)

- Clearly scoped AI actions (AI changes are atomic and infrequent)

- Clear attribution (users can always tell what changed and why)

…a linear undo stack is still the correct choice. Don't over-engineer.

The Product Engineering Principle: Graph-based UX is not a free upgrade. It's a commitment—to more complex code, higher cognitive load, and ongoing maintenance. Make that commitment only when the system's edit rate and actor count demand it.

The Real Axis: Edit Rate × Number of Actors

The breaking point isn't "AI" — it's scale of interaction. This is what I wish I'd understood earlier: the problem isn't AI specifically, it's the multiplication of edit rate and actor count.

Two variables matter most:

1. Edit Rate

- Frequency: How many operations per minute/second?

- Pattern: Are changes bursty (user typing), continuous (auto-save), or background (sync)?

- Volume: How much state changes per operation (character vs. paragraph vs. section)?

As edit rate increases, the window for "last operation" ambiguity shrinks. At high rates, multiple agents' operations interleave constantly, making attribution impossible without explicit tracking.

2. Number of Independent Actors

- Humans: Multiple collaborators editing simultaneously

- AI agents: Single or multiple AI assistants with different scopes

- Automations: Background processes, auto-formatting, validators

- Integrations: Webhooks, API updates, sync from external systems

Each actor adds a dimension to the state space. Two actors create a 2D timeline. Three actors create branching complexity. Four+ actors create graphs that linear stacks can't handle.

The Degradation Curve

At low levels (edit rate < 1/min, actors ≤ 1):

- Ambiguity is rare (single-user, infrequent edits)

- Errors are tolerable (users notice and recover quickly)

- Trust recovers quickly (predictable behavior)

- Linear stacks work fine

At medium levels (edit rate 1-10/min, actors 2-3):

- Ambiguity becomes common (who changed what?)

- Errors become frustrating (unpredictable undo behavior)

- Trust starts eroding (users question system reliability)

- Linear stacks start breaking

At high levels (edit rate > 10/min, actors 4+):

- Undo becomes unpredictable (high probability of wrong operation)

- Redo becomes meaningless (no clear "forward" direction)

- Users stop experimenting (lose safety net, become risk-averse)

- Linear stacks actively harm UX

This is where graphs stop being "nice to have" and become infrastructure—the foundation your product needs to function correctly in multi-agent environments.

Product Engineering Takeaway: Don't build graphs because they're cool. Build them because your edit rate × actor count has crossed a threshold where linear systems fail. Track these metrics, know your breaking point, and invest in complexity only when the data shows you need it.

This research comes from years of building collaborative editing systems and watching undo/redo break in production. It's part of ongoing work at Legit, where we're building infrastructure for AI collaboration with control.

Agent UX is one of the most exciting and under-explored areas in product engineering today. If you're wrestling with similar challenges—undo/redo, attribution, user agency in multi-agent systems, or how to scale collaborative interfaces—I'd love to hear from you. This is a space that needs more builders, more experiments, and more shared knowledge.